Determining and explaining the causes and results of change in a period of history is a common task for historians or teachers. For the striking period of history from the end of the Anti-Japanese War in 1945 to the Communist Party of China (CPCP) seizure of mainland power from the Kuomintang (KMT) in 1949, historians have proposed research, analysis and explanations from different perspectives in the fields of politics, economy, military studies, culture and society. The historical roles played by the words and deeds of individuals such as Chiang Kai-shek, Mao Zedong and United States (US) President Harry Truman during this period have also been described in detail in different biographical histories. We know that historians have different degrees of complaint about the long-term archive control exerted separately by the KMT and the CPC. However, even today, the partial opening of national archives and their use by researchers have produced comforting results, but no surprising historical revelations resulting in new conclusions.[1] Based on the individual researcher's knowledge and background, his or her values (or political stance), and the documentary resources he or she can access, different interpretations of history, as of those regarding the ‘civil war’ discussed in this article, are inevitable.

Historians usually understand, analyse and judge the Chinese Civil War (1945-49) and its outcome by drawing on several issues. The first thing they deem needs to be understood and analysed about the Civil War is the issue of war and military conflict. The military defeat of the KMT in the decisive battle with the CPC during the Civil War indeed became a historical symbol – it was its military defeat that caused the KMT to lose its power on the mainland. Many historians have studied the military conflicts of the Civil War, especially the military strategies and tactics of the KMT and the CPC, to analyze the reasons for the KMT's failure. However, this approach does not fully explain why the KMT army, which was the main force in the Chinese Anti-Japanese War and still had far stronger military power and resources than the CPC after 1945, was defeated by the CPC army in just four years (see Table 1).

![Table 1. Comparing the Relative Power of the KMT and CCP at the outbreak of the Civil War (July 1946) [2]](/_astro/47362df689348535b984d5666197fec4397b49e6-1080x400_Z14Qc8D.avif)

At the same time, it cannot effectively explain why the CPC did not eventually achieve the complete annihilation of Chiang Kai-shek's army, as a result of which the KMT soon gained a foothold in Taiwan and achieved progress and development in politics, economy, culture and other social fields. In the analysis of war and military factors during the Civil War, the development of the strength of the CPC's army must be studied before and after the major Chinese political crisis of the Xi'an Incident of 1936, and the increasing strength of the political strategy of the CPC must also be seen in the context of the Japanese invasion of China.

Because military conflict during the Civil War was an external manifestation of complex political struggles, the measures taken by the KMT and the CCP in dealing with domestic politics and their results show the changes in the power of both sides during the four years of the War. This was especially evident in 1947, which was the year when the CCP changed from strategic passivity to strategic initiative. Before that, the CCP promoted the democratic movement in urban policies, called for the establishment of a coalition government, and reduced rent and interest in rural areas (initially in the ‘old liberated areas’ of the CCP, and then into the ‘newly liberated areas’ after the victory of the Anti-Japanese War) in the period until the land reform movement initiated by the ‘May 4th Directive’.

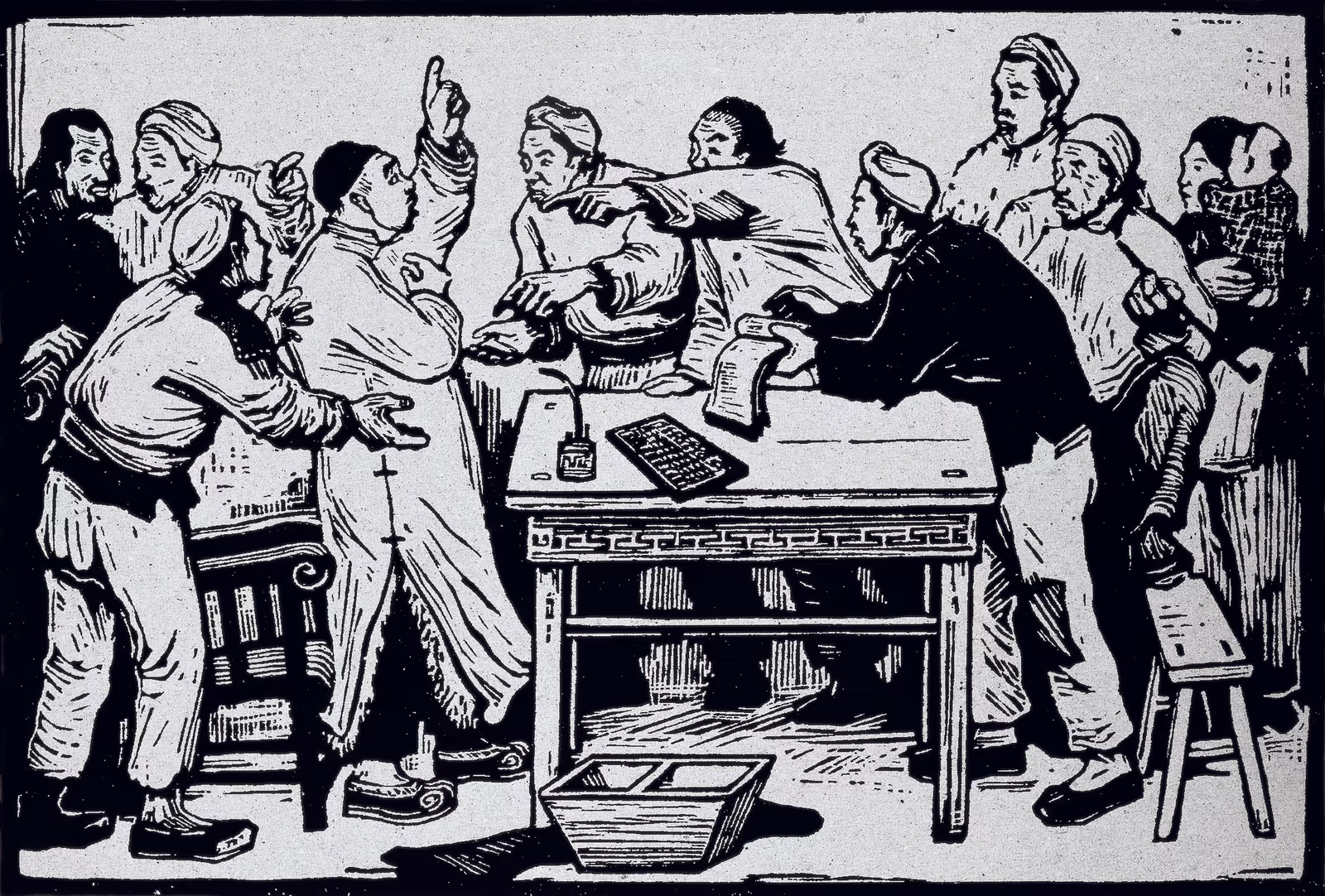

Among the CCP’s related policies, the confiscation of the land of landlords, especially large landlords, can be seen as a very effective step in the CCP waging political struggles with the KMT. Some scholars have demonstrated that the CCP was mainly eliminating the landlord class through the ideology of ‘class struggle’, because in some areas where the land ownership gap between farmers and landlords was not large there was nevertheless severe class struggle, which entailed the denunciation and even suppression of landlords and rich peasants, as well as the deprivation of their freedoms.[3] In fact, the result of ordinary farmers obtaining land (that realised benefits) obviously led to their support for the CPC, which ranged from individuals joining the army to families providing logistical and material services for the CCP's military struggle. In fact, with the support of the ‘barrel of the gun’ that Mao Zedong most valued, the propaganda of the CCP ideology and the transfer of property and land from the landlord class to ordinary peasants were mutually supportive and integrated, and neither was dispensable. Data shows that it was the land reform movement of the CCP in different stages and regions that provided obvious and direct support for the increase of the CCP's military personnel and necessary war materials. The CCP formulated policies to reduce contradictions and increase sympathy and understanding in the process of implementing land reform in various places. However, land reform, as a class struggle campaign, subverted the rules and power groups that previously protected the interests of landlords and rich peasants in local and rural areas against the background of the CCP's growing military power. It then fundamentally destroyed the institutional power of the landlord class.

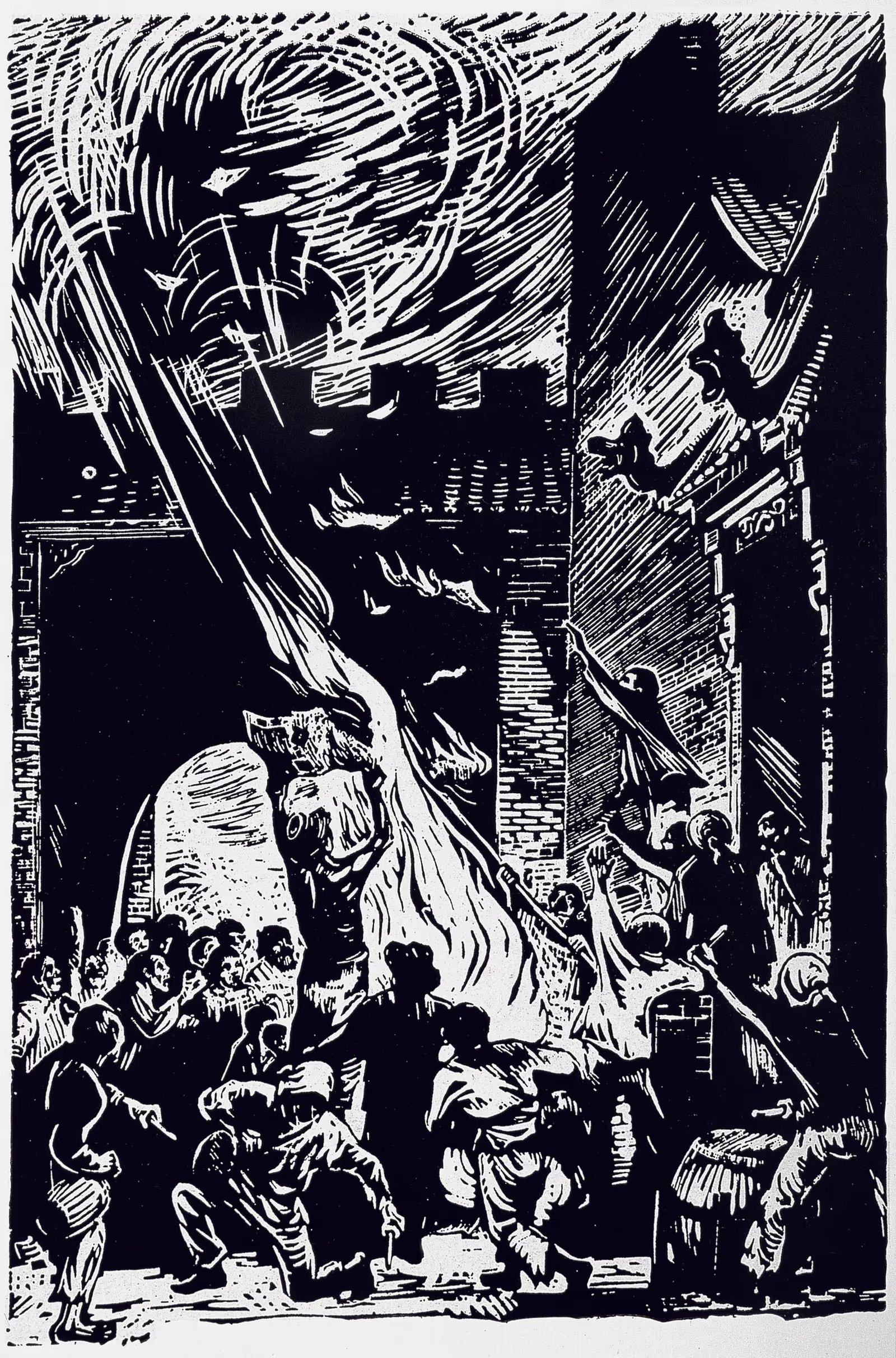

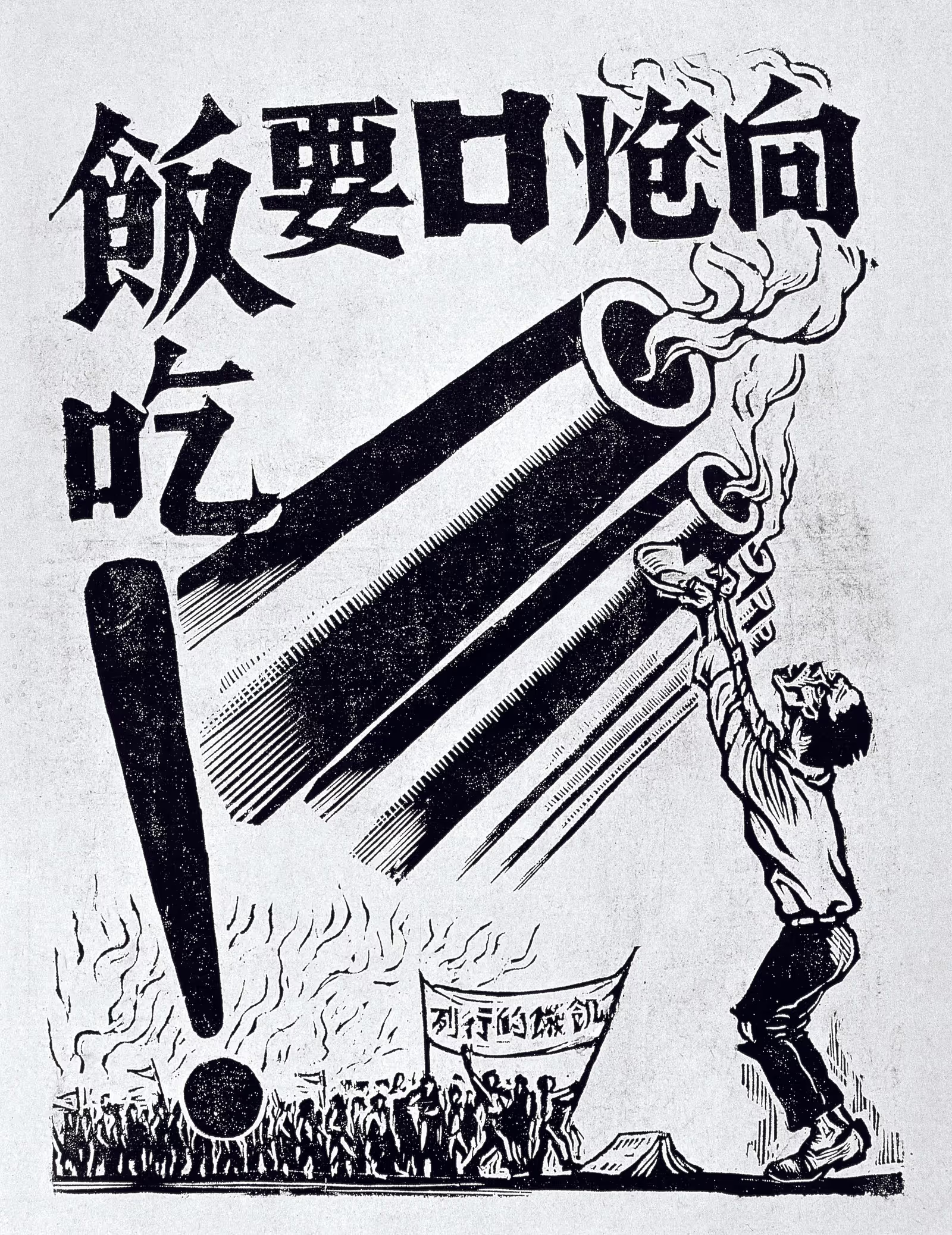

In the art of Yan'an, especially the woodblock prints, the political themes of ‘rent and interest reduction’ and the burning of land deeds were frequently depicted (see for example, Figure 1). At the same time, the CCP emphasised in its political propaganda that the invasion of imperialism plundered the Chinese people, and that it was the KMT’s ‘collusion’ with imperialism that had led to the impoverishment of China’s peasants. Therefore, the CCP, with the support of its armed forces, relied on ideological propaganda rather than on the type of land policy. which was only later implemented by the Kuomintang in Taiwan and which allowed farmers to obtain land through the rules of exchange. This was indeed one of the important reasons why the CCP’s troops and war materials continued to increase, while the Kuomintang’s manpower and material resources continued to decrease. It is also the reason why the CCP’s army ultimately won the war. Indeed, the land revolution began as early as the 1930s, long before 1945. From rent reduction and interest reduction to a more radical and risky approach that entailed burning land deeds and confiscating landlords’ land, the land revolution expressed the strong demand by the CCP to abandon the previous coalition government that saw them struggle for partial power and the CCP’s determination to seize state power as soon as possible.

Although the CCP had formulated a strategy aimed at easing conflicts, this proved less effective than direct confiscation of land holdings. The CCP held that the KMT represented the landlord class and did not take violent measures against rural landlords (unlike the CPC). When the conflict between the KMT and the CPC became public, those officers who came from the rural landlord and rich peasant classes obviously became enemies that had to be eliminated in campaigns characterised by ‘striking down local tyrants and dividing the land’, rather than objects of protection as they had been in the early land reform period of the 1920s and 1930s.

Those influenced by the CCP in the cities, a group mainly comprising workers, students, and intellectuals, were difficult to quantify. This was not only because the cities were mainly controlled by the KMT, but also because the police, capitalists, financial circles, citizens, and the floating population were all under the KMT's political and public opinion control. Examining the impact of its economic failure and corruption of power on society and public opinion may not be enough to explain why the KMT ultimately failed in the Civil War. Although the CCP and other parties had previously had an influence in striving for democracy and promoting the formation of a coalition government, during the KMT's takeover of the Northeast, the killing of Zhang Shenfu (an incident fabricated by the CCP) triggered protests from students and intellectuals across the country who yearned for freedom of thought. It also showed that people made their own independent judgements on real politics, and did not completely lean towards either the KMT or the CCP at the beginning.[4]

During the Civil War, the students' anti-hunger and anti-civil war movements simply expressed the hope that the KMT, CCP, and various other party organisations would establish a coalition government as soon as possible. The Shanghai-based Southeast Daily 《东南日报》(24 December 1948) published a survey report on the KMT-CPC dispute involving 1,000 students and teachers: 15.9 per cent of people were in favour of carrying the anti-communist war through to the end, 72 per cent were in favour of establishing a coalition government, 8.4 per cent believed that China should be divided, and only 3.7 per cent were in favour of the Communist Party's one-party dictatorship.

The CPC also reservedly used and encouraged student movements that it believed included participation by intellectuals. Indeed, when the KMT’s rule was increasingly plagued by political, economic, and military problems, the CCP’s accusations and political propaganda played a clear role in inciting the growing popular dissatisfaction with the KMT’s governance capabilities. Moreover, the KMT’s urban media also published information about corruption and, at the same time, the KMT’s brutal measures against the students’ anti-war movement gradually pushed students toward the CCP, until intellectuals and the public increasingly inclined to hope that the CCP would take over from the KMT regime. However, should the legitimacy of the new post-war regime also be tested against the degree to which the public, and society overall, were satisfied with the CCP’s rule – seemingly ushering in security, peace, rule of law, and freedom from hunger – after taking over the KMT’s political resources?

After 1949, the discussion in the US about ‘why we lost China’ was not meaningless, as some people later believed. T. A. Bisson's prediction after visiting Yan'an, John Stewart Service's advice to General Joseph Stilwell, or John Leighton Stuart's last-minute expressed expectations for the CPC, as well as the subsequent discussion about ‘losing China’, were all verified by subsequent historical facts to have raised many issues worth discussing. Examining the evolution of China's modern history without considering China and the US (and other Western countries) is not in line with effective historical analysis today.[5]

The problem is not that the discussants must be clear that China and the US are two countries, and whether China's historical problems should be found in China's internal factors, but, since the nineteenth century, could China's problems really be simply considered to be caused only by China's internal factors? (especially after the arrival of George Macartney's mission to China). The defeat of the KMT and the victory of the CPC in the Civil War not only involved the reasons mentioned above, but also had something to do with the goals, judgements and decisions of the US after 1945. This view is also supported by the fact that, a few years later, the KMT in Taiwan was protected by the US Seventh Fleet and thereby gained security, stability and room for development. In fact, during the Civil War, both the US and the Soviet Union played important roles. The US shifted its focus to combating communism from China to North Korea, and the Soviet Union cooperated with the CPC in the process of dealing with the nationalist government. We can find obvious traces of influence of both the US and the Soviet Union in the historical process and even the turning point. Certainly, they participated in the shaping of the history of the Civil War. The related issues remind us that the victory of communism in China in 1949 needs to be viewed as more than a political label or slogan. In fact, the Soviet model adopted by the CCP shows that China was a special social form with Marxism as its flag, and it established a one-party authoritarian political system that was seriously influenced by the Soviet Union. This understanding will in turn make us more aware of the complexity of the conflict between the KMT and the CPC from the 1920s onwards, given that the political strategies adopted by the CCP in different historical periods were not consistent with its ideological program.

Conclusion

The study of the 1945-49 Chinese Civil War and its outcome cannot be separated from the historical context before 1945. The political strategies of both the KMT and the CCP, the social factors they faced, and the international background all prepared the conditions for China after 1945. Events that have already happened cannot be deduced from hypothetical conditions, and historical analysis should be focused on the context of specific historical reality. Even when the KMT incorporated the CPC army into its own organisation during the Anti-Japanese War, to fight the common enemy together, the development of the Eighth Route Army and the New Fourth Army directed by the CCP in Yan'an was largely based on the KMT’s opposition to the Japanese army on the battle front. Mao Zedong's repeated ‘thanks’ to Japanese leaders post-1949, and the continuous revelations of information, show that communist ideas or moralistic ideals were not the tools the CCP used to achieve victory step by step.

At the same time, after the Japanese army entered the three northeastern provinces in 1931, the economy under the rule of the national government seemed to be worsening. Corruption in officialdom and the army, as well as social and economic decay, were associated with problems in the KMT's governance. However, from the Northern Expedition in 1924 to the failure of the first period of cooperation between the KMT and the CCP in 1927, the period of social construction by the KMT government lasted slightly less than ten years (1927-37), during which time there was still resistance from the CCP armed forces and political sabotage by underground organisations.

After 1937, during the second period of cooperation between the KMT and the CCP due to the Anti-Japanese War, the CCP used guerrilla warfare, land movements and urban political strategies to protect its own strength as much as possible and to avoid the frontline battlefield. All these elements determined that the KMT could not achieve mature governance and resource-rich national construction. It should be emphasised that the problems faced by the KMT and the CCP were the same – preventing provincial (warlord) autonomy, maintaining social order, developing the economy, and facing Japan's powerful military aggression.

After 1978 the economic reforms initiated in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) seemingly extended the possibility of re-examining China to those who study modern Chinese history. However, this optimism lacked the historical understanding that the economic reforms and political relaxation brought about by this reform only permitted the CCP to truly understand and interpret the lessons and experiences of its history, rather than following world trends, choosing goals in line with those of most countries in the world (especially Western developed and advanced countries), and setting goals and strategies to achieve them in line with the interests of its own people and the people of the world. Neither the CCP, the KPC, nor the Democratic Progressive Party can represent this country or China including Taiwan. During the Civil war, the KMT and especially the CPC claimed to represent China, but the historical ‘great achievements’ claimed by the two parties at different stages of history are questionable. Deception, lies, conspiracies, and inconsistencies between words and deeds exist in the form of ‘strategies’ in major events at different historical stages. Therefore, in terms of the standards of human civilization, 1949 can only be regarded as the adjustment of the positions of the KMT and the CPC, and it is difficult to express it as historical progress. Today, when the CCP faces institutional challenges again, it will not face the same situation that the KMT did in the 1970s.

Finally, the military confrontation between the KMT and the CPC after 1945 makes it difficult for either side to win sympathy in terms of historical justice or for their moral standpoints. In fact, to this day, the war between the KMT and the CPC has not ended. Taiwan and the mainland each strictly maintain and use their own archives and try to narrate history according to the political needs of different periods. It is doubtful whether ‘historical conclusions’ that are closer to the truth will be drawn because of any continuous opening of these archives. The historical view and value standpoint always affect the judgment of researchers – even for foreign scholars working in quiet environments far removed from any external disturbance. Of course, the Civil War in 1949 not only changed the Chinese mainland, but also, obviously, changed the world pattern. This is a fait accompli . Therefore, historical judgements based on results will always find materials that conform to a perceived necessity to prove a stance. However, there is no inevitability in history, only the inevitability of writing and creating history - this is why the CPC always uses historical documents that it deems useful to prove that it is a great, glorious and correct party.

Reference:

[1] 1Open archives are undoubtedly helpful for historical research. However, based on today's historical methods and concepts filtered through the changes in the field of philosophical thought, the analysis and treatment of data and documents will obviously not fall into the trap of historical essentialism. Time and new discoveries of data may certainly change people's views on the past to varying degrees, but does this mean that our views on history from decades ago have completely changed? Not to mention reaching a consensus among researchers. For example, the periodisation of the Chinese Civil War will not be agreed upon simply because of the discovery of new materials.

[2] Zhang Xianwen et al., A History of the Republic of China , Vol 4, (Nanjing University Press, 2005); Peking University, International Politics Department, Selected Statistical Data on Modern Chinese History (Henan People's Publishing House, 1985), 396.

[3] There are many data and documents on peasants joining the army or militia organisations led by the CPC during the land reform period. For example, in August, September, and October 1946 alone, 300,000 peasants in the Suzhong Liberated Area joined the CPC army, and three to four million joined militia organisations. In Ningnan County in southern Hebei, 130,000 peasants participated in the land reform, and each person received an average of 2-3 mu of land. The CPC required no less than 800 people to join the army. However, after mobilisation, 3,200 people in the county signed up to join the army within ten days ( People’s Daily 《人民日报》, 29 March 1947). From July 1946 to the end of 1947, in the early days of the civil war, 1.2 million civilians in the Hebei-Shandong-Henan region supported the front line [Qi Wu, The Growth of a Revolutionary Base Area , Beijing People's Publishing House, 1957 edition, 289(齐武:《一个革命根据地的成长》北京人民出版社1957年版,第289页)].

[4] On 16 January, Zhang Shenfu, the Northeast Acceptor of the Ministry of Economy, who was sent by the Nationalist Government to participate in the repatriation from the Japanese of organisations and enterprises in the Northeast, contacted the Soviet side to discuss the acceptance of the Fushun Coal Mine. On the evening of the same day, Zhang and his entourage were killed by the Soviet army and the CPC when they returned to Shenyang from Fushun via Lishizhai Station. However, the CPC issued an internal instruction (25 February) stating that the KMT ‘colluded with the Japanese to create the Zhang Shenfu tragedy as an excuse to oppose the Soviet Union and the Communist Party’. When the Zhang Shenfu tragedy was disclosed at the end of the month, from 22 February to early March, students and intellectuals in major cities across the country, starting from Chongqing, launched large-scale demonstrations against the Soviet Union and the CPC. Famous participants included Wang Li, Zong Baihua, Shen Congwen, Wu Dayou, Chen Xujing, Feng Youlan, Tang Yongtong, Fu Sinian, Wang Yunwu, Chu Anping, Huang Yanpei, Shen Junru, Zhang Junmai, Chen Daisun, Gu Jiegang, Qi Sihe, etc. (See Lü Peng, A History of China in the 20th Century , Chapter 4, Palgrave Macmillan, 2023).

[5] In July 2020, then-US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s speech at the Nixon Library can be seen as a continuation of this earlier discussion, or even a conclusion, fifty years later. Pompeo’s speech was seen as the opening of a new Cold War and a new Iron Curtain, because he emphasised the fundamental differences between the Chinese Communist regime and Western countries in ideology and political system. In this speech, Pompeo made a very clear distinction between the ‘CPC’, ‘China’ and the ‘Chinese people’. In fact, the 2018 US-China trade war and the subsequent policy adjustments toward China were the result of a joint review of history by the Republicans and Democrats. This was actually a very late response to the early discussions about China’s ‘fall’ to communism.